George Takei, of “Star Trek” fame, lost his freedom in 1942 when he was 5 years old.

Granted, most 5-year-old kids don’t have much freedom. But it’s how Takei lost his freedom that he can’t forget. He doesn’t want you to forget it, either.

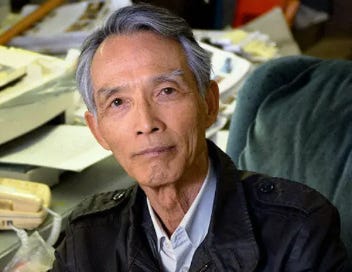

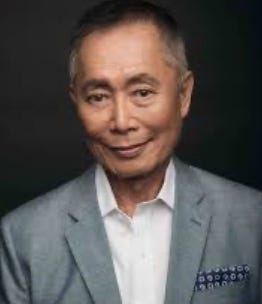

“I’ve told this story many, many times. It is an important chapter of American history,” Takei told James Bash, a journalist writing for The Oregonian. “But it always takes me by surprise whenever I talk about my childhood imprisonment. People are shocked that this actually happened.”

Then Bash uses words with a different historical context: “Takei was referring to the incarceration of Japanese Americans after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941. That unleashed a tsunami of anti-Japanese sentiment, which swept over the nation and unjustly sent 120,000 Japanese Americans to concentration camps.”

Concentration camps?

I’ve visited Manzanar, and I’ve seen Dachau. There is no comparison. Had Takei’s family been sent to Dachau, Auschwitz, Buchenwald, Bergen-Belsen or other WWII concentration camps, he likely would have never reached adulthood — let alone had a celebrated career as a Hollywood actor.

Takei wrote a picture book called My Lost Freedom, and it has been put to music by composer and violinist Kenji Bunch of Portland. This weekend it was scheduled to be performed by the Chamber Music Northwest at Reed College in the Kaul Auditorium. It’s a chamber piece with Takei providing narration. It was sold out.

I missed buying a ticket, but on Friday there was a free open rehearsal at 11 a.m. It was a beautiful, sunny spring day on a campus known for its expansive Great Lawn and famous former student Steve Jobs. (It’s a myth that the college is named for Portland’s most famous radical, John Reed. He graduated Harvard).

Almost 90 people turned out to listen to the rehearsal featuring two violins, viola, cello, piano, and percussion. Takei was not present, but there was a Q-and-A between the audience, the composer and a few of the musicians.

A woman asked about the collaboration between Takei and the composer. “Was it just you and George?”

“Yes, just me and George. I read his book. We talked a lot,” Bunch said.

Bunch has Japanese heritage, and in 2015 visited the Minidoka internment camp in Southern Idaho. He walked around by himself, looked at some of the buildings that had been preserved and felt inspired to write a small piece for viola called “Minidoka.”

Bunch performed the piece for the Moab Festival’s music director, who suggested a larger piece on the same topic and said he could get Takei involved.

That led to Bunch meeting Takei. Their collaboration became Lost Freedom: A Memory.

He told the rehearsal audience, “One thing important to both of us, we weren’t interested in any explicit Japanese influences in the sound of the music. (It’s) definitely an American story (and) required American-sounding music. … the sound of his childhood.”

They didn’t want it to be specific to a particular community, a very small community of people at that.

“One of the things everybody has in common regardless of anything else is at some point we were all children…,” Bunch said. “Dependent on older people, trusting them, scared, confused. These are universal emotions.”

The point was to try and avoid something like the internments from happening again.

Takei, who is 88, continues to tell others about what happened in 1942. He worries that America today is exhibiting similar behavior — promoting intolerance instead of understanding.

“Some people learn, but many don’t, and that can cause us to repeat history all over again. Many people are slow to accept the fact that America’s strength is its diversity,” Takei told Bash in The Oregonian.

What does history teach us about Japan’s lack of diversity? It was very much a mono-culture, an island isolated from other cultures. The Japanese considered themselves a superior race.

If you weren’t Japanese, you were less than human. That included Koreans, Chinese, Filipinos, Americans — all inferior to the Japanese.

What does George Takei know about the Rape of Nanking? What does he know about the Bataan Death March?

What does he know about the Korean comfort women forced to service the Japanese Imperial Army? What does he know about Unit 731?

For that matter, what did the audience at the open rehearsal in the Kaul Auditorium on the Reed College campus know about any of those historic events? Did they know that during the Reagan Administration, the U.S. paid reparations to the Japanese who were interned?

It would be impossible to fully restore what Japanese-Americans lost while interned, but it’s more than what the Japanese offered the Chinese, the Koreans, the Filipinos — victims of unbelievable atrocities that Japanese leaders seemed loathe to even apologize for. Atrocities that far outnumbered the dead at Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

When a virtual unknown from Missouri named Harry Truman crushed Japanese superiority, Emperor Hirohito refused to even utter the word “surrender.” (Post-WWII, Hirohito was allowed to remain in office.)

What does George Takei have to do with the Rape of Nanking, the enslaved comfort women, the Bataan Death March, Unit 731? No more than Donald Trump’s deportations of illegal immigrants have to do with America’s Japanese internment camps.

Yet, here came a question/comment at Reed College’s open rehearsal from a woman.

“I cried through most of it … It was beautiful,” she said, and then she ventured sheep-like into safe territory by referencing today’s “threat to democracy.”

Presumably, she wasn’t talking about the $1.5 billion debt the state of Oregon is facing providing health care for illegal immigrants — people who ignored our borders and immigration laws.

What would George Takei’s father make of that generous welcome mat?

When Takei’s family was released from the internment camp, they started with nothing. His father had previously owned a successful dry cleaning business. The only job he could find upon release was as a dishwasher in a restaurant owned by Asians. Only Asians would offer him employment.

Here’s a portion of the backstory on America’s Japanese internment camps that the Reed audience might not want to be reminded of. It was a progressive Democratic president — Franklin D. Roosevelt — who ordered the internments.

Historian Doris Kearns Goodwin notes in her book, No Ordinary Time, “If Roosevelt shrewdly understood the strength of America’s democracy, he failed miserably to guard against democracy’s weakness —the tyranny of an aroused public opinion. As attitudes toward Japanese Americans on the West Coast turned hostile, he made an ill-advised, brutal decision to uproot thousands of Japanese Americans from their homes… . The atmosphere of hatred gave license to extremist elements.”

Goodwin highlights another issue.

“Economic cupidity also played a significant role. … Though Japanese-owned farms occupied only 1 percent of the cultivated land in California, they produced nearly 40 percent of the total California crop.”

In other words, envy of the Japanese and the farmland they diligently worked. It resembled the same envy that Germans visited upon successful, hard-working Jews.

Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 required the forced removal of all people of Japanese descent from any area designated a “military zone.” That included the entire state of California, the western half of Washington and Oregon and the southern part of Arizona.

He would later regret his decision. But thanks to Memory Activists like Takei it has not been forgotten.

The same cannot be said of the thousands who died on the Bataan Death March or the thousands of anonymous Korean girls and women forced into sexual slavery or the roughly 300,000 people who died in the Rape of Nanking or the thousands of anonymous men, women and children who all died from hideous medical experiments in Unit 731.

How many of these history lessons are taught in high school?

In a 1998 interview with The Straits Times of Singapore, Iris Chang described her reasons for writing The Rape of Nanking.

“I wrote it out of a sense of rage,” she said. “I didn't really care if I made a cent from it. It was important to me that the world knew what happened in Nanking back in 1937.”

For a time, the book was a best-seller. But Chang ended up having a nervous breakdown. She committed suicide in 2004 when she was 36. She had begun work on another book — this time about the Bataan Death March.

At the time of her death, journalist Orville Schell compared the Japanese acknowledgment of what they did in Nanking to “little fragments and shards and bits and pieces. But no one has done what Willy Brandt did: got down on his knees in the Warsaw ghetto and asked forgiveness.”

What did the Japanese do in Nanking? Whatever they wanted to. They rampaged and tortured. Raped children and grandmothers. Murdered all men on sight. Destroyed a third of the city.

“(T)he Japan Advertiser, actually published a running count of the heads severed by two officers involved in a decapitation contest, as if it was some kind of a sporting match.”

What would Chang have made of the events of Oct. 7, 2023 when Hamas terrorists attacked Israel — killing, raping and taking hostages? Would she have seen history repeat itself?

Then there is Unit 731, which it’s fair to say is probably unknown to many Americans.

This germ factory in Harbin, China is where 3,000 Chinese, Korean and Russian men, women and children were used for experiments by the 731st Regiment of the Japanese Imperial Army.

The human guinea pigs were referred to as “logs” because they were the basic building blocks for research.

In 1981, Japanese writer and pacifist Seiichi Morimura, who tracked down and interviewed workers at Unit 731, wrote The Devil’s Gluttony, which became a best seller in Japan. Among some of the experiments:

Victims were exposed to pathogens — including plague, typhus, cholera, syphilis and anthrax. Naked men were subjected to freezing temperatures for long periods to freeze their flesh and limbs, which were then pounded with boards to measure their sensitivity. Other victims underwent transfusions with horse blood. Some were exposed to X-rays for prolonged periods. Still others were locked in a pressure chamber to see how long it took before their eyes popped out of their sockets.

“This story should be told to all Japanese, to every generation. Japanese aggression should be written about to prevent another war,” Morimura said.

When he died in 2023, The New York Times quoted from an interview he had given to a newspaper in Melbourne, Australia: “Almost all Japanese war themes are from the standpoint of Japan as a victim, but mine is from the point of view of Japan the transgressor doing violence against other nations.”

Unit 731’s leader, Lt. General Shiro Ishii and other officials, were granted immunity from prosecution as war criminals by the U.S. in exchange for Americans’ obtaining the data and results from Japan’s experiments in using germs as lethal weapons.

The Japanese experiments with biological weapons enabled them to confidently set a target date of Sept. 22, 1945 to contaminate San Diego with plague-infested fleas. That plot became irrelevant after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on Aug. 6 and Aug. 9.

Ishii lived peacefully until his death by throat cancer in 1959. Many of those who worked closely with Ishii went on to prominent careers — Governor of Tokyo, president of the Japan Medical Association, head of the Japan Olympic Committee.

In 1995, New York Times reporter Nicholas Kristof also wrote about Unit 731. Like Morimura, he interviewed people who had helped conduct the experiments.

“The accounts are wrenching to read even after so much time has passed,” he wrote.

One man he interviewed performed surgeries on adults and children without anesthesia — to better study how the body organs and blood vessels react. He detailed cutting into his first human guinea pig.

“I cut him open from the chest to the stomach, and he screamed terribly, and his face was all twisted in agony. … He made this unimaginable sound, he was screaming so horribly. But then finally he stopped.”

Kristof describes him as smiling genially.

The man explains: “There’s a possibility this could happen again because in a war you have to win.”

There's nothing quite so pathetic as a former star clinging to the spotlight...followed closely by an audience that doesn't have the will or brainpower to do their homework. It's this numb, self-indulgent, narcissistic thinking that has helped to produce the state and city we live in.

History matters.

The belief in many cultures (over millennia) is that there are two deaths; the physical death of an individual and the last time anyone remembers and states the name of the now departed person.

The US was complicit in preventing ANY accountability for the war criminal of Unit 731, even more so than Nazis like Werner Von Braun (who held the rank of Sturmbannfuher in the SS in 1943, equivalent to Major in the regular German Army - Wehrmacht)